When his 6 years old induction cooker recently broke, [Johannes] decided to open it in an attempt to give it another life. Not only did he succeed, but he also added Bluetooth connectivity to the cooker. The repair part was actually pretty straight forward, as in most cases the IGBTs and rectifiers are the first components to break due to stress imposed on them. Following advice from a Swedish forum, [Johannes] just had to measure the resistance of these components to discover that the broken ones were behaving like open circuits.

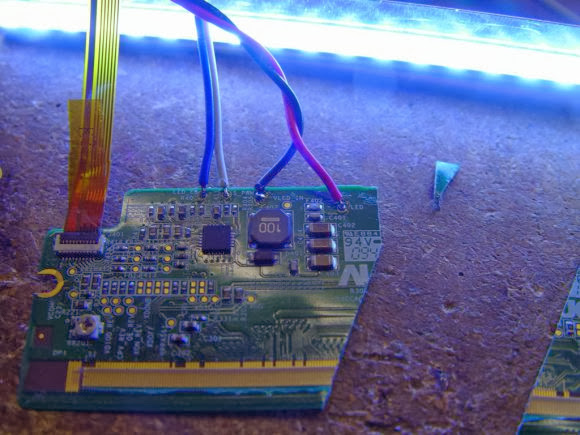

He then started to reverse engineer the boards present in the cooker, more particularly the link between the ‘keyboards’ and the main microcontroller (an ATMEGA32L) in charge of commanding the power boards. With a Bus Pirate, [Johannes] had a look at the UART protocol that was used but it seems it was a bit too complex. He then opted for an IOIO and a few transistors to emulate key presses, allowing him to use his phone to control the cooker (via USB or BT). While he was at it, he even added a temperature sensor.

He then started to reverse engineer the boards present in the cooker, more particularly the link between the ‘keyboards’ and the main microcontroller (an ATMEGA32L) in charge of commanding the power boards. With a Bus Pirate, [Johannes] had a look at the UART protocol that was used but it seems it was a bit too complex. He then opted for an IOIO and a few transistors to emulate key presses, allowing him to use his phone to control the cooker (via USB or BT). While he was at it, he even added a temperature sensor.